Predicting Flight Cancellation - Python

Published:

Apply Machine Learning on a publicly available dataset that describes worldwide Flight Status information from 2018-2021 to predict whether a flight is cancelled or not.

Overview:

- Research Project prepared for COSC3117 Artificial Intelligence - Algoma University.

- Repository located at the following link

https://github.com/erincameron11/PredictingFlightDelay

Dataset:

The dataset for this project can be found on the website Kaggle (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/robikscube/flight-delay-dataset-20182022). Data files were not uploaded to the GitHub repository due to the large size of the files (over 4GB). A subsetted dataset which was used for model predictions can be found linked on Google Drive: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1wuc2VTNImHGBc6Z7_AY9Rlj1mRAS8jYu/view?usp=share_link.

Objective:

The aim of this project is to use a publicly available dataset that describes worldwide Flight Status information from 2018-2021 to predict whether a flight is cancelled or not. The classification algorithms I chose for this project are: Logistic Regression (LR), Naive Bayes’ Classifier (NBC) and Random Forest (RF). All three models were implemented using Python’s scikit-learn machine learning library.

Although all three of the chosen algorithms (LR, NBC and RF) will ultimately classify each flight as cancelled or not cancelled, the underlying methods and approaches to classification vary. In general, NBC works better with smaller datasets, while LR works well with larger datasets. LR and RF work better with collinearity (independent variables), since NBC assumes independence among features. NBC predicts classes of datasets much faster than LR and RF. NBC can also predict multiple classes.

Similarly to different styles of classification algorithms, there are several commonly used metrics to describe various aspects of classification performance (ie. how many flights were correctly classified as cancelled?) after the model has been trained and predictions have been performed. There are also several metrics employed to evaluate which features are the most informative for predicting flight cancellation status – otherwise known as “feature importance”. I examine these metrics later on.

The general outline of this project will be: (1) clean and explore the dataset to select features and flag missing data points , (2) apply three machine learning algorithms to classify flights as cancelled or not, and (3) evaluate each model for accuracy and compare performance across algorithms.

Data Cleaning and Exploration

File: 1_Data_Cleaning_Exploration.ipynb

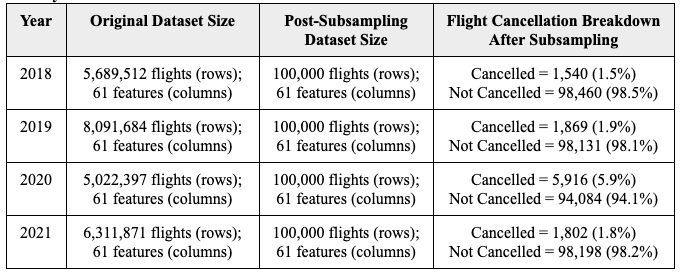

After downloading the dataset, I loaded data for each year (2018 - 2022), randomly subsampled the data to 100,000 flights (rows) per year and merged data across years into a single file using the pandas3 data manipulation Python package. Random subsampling was necessary because the original yearly data frames were very large (>3 million flights per year), making it challenging to compute and work on such a large dataset (Table 4). Additionally, I excluded the year 2022 because data is not available for the entire year, and therefore is not representative of yearly flight data. Together, this resulted in a final dataset of 400,000 flights (rows) and 61 features (columns) across 4 years from 2018 to 2021. Many of the 61 features have redundant information and are not truly independent of each other (ie. airline name vs. airline abbreviation), resulting in less than 61 informative features in the dataset.

I explored features in the dataset and performed various data cleaning tasks, such as handling missing variables. First, I investigated the nature of the “Cancelled” column, which contains the variable I am interested in predicting – whether or not a flight will be cancelled. In the subsampled data of 400,000 flights –11,127 (2.8%) flights were cancelled and 388,873 (97.2%) were not cancelled. Next, I checked to see if there are any missing values in the Cancelled columns. There were no missing “NaN” values in the column, indicating that I do not need to remove any additional rows from the data.

Breakdown of randomly subsampled dataset and number of cancelled flights across years:

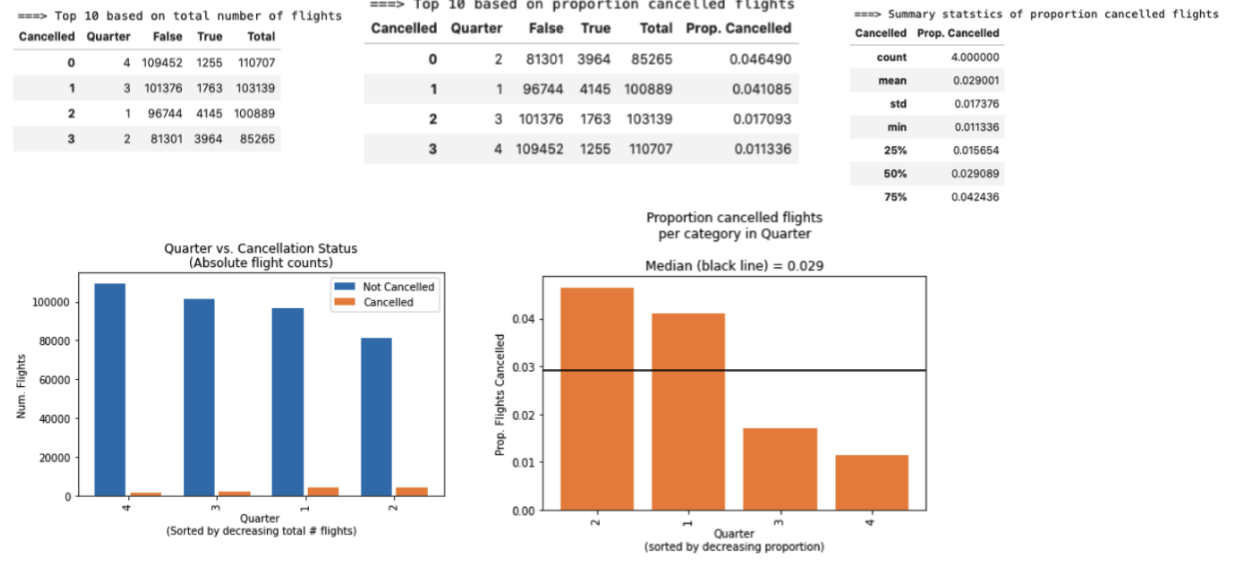

Next, I investigated how the “Cancelled” feature relates to other data features/categories in the dataset. For each of the remaining features in the dataset, I investigated the available values within each column, the frequency of these values and checked for missing values. First, I focused on visual assessment of the relationship between categorical variables/columns and flight cancellation status. This will give us clues as to which features may be predictive or associated with cancelled flights. Specifically, I examined the following categorical features: “Airline”, “OriginStateName”, “OriginCityName”, “DestCityName”, “DestStateName”, “Year”, “Quarter”, “Month”, “DayofMonth”, “DayOfWeek” and “Marketing_Airline_Network”. Alongside several summary statistic tables, I used the matplotlib4 and seaborn5 Python package to plot two different visualizations for each categorical variable: (1) absolute number of cancelled or not flights, to get a sense of number of events within categories and (2) proportion of flights that are cancelled within groups of each variable, which will more clearly highlight differences, since cancelled flights only represent 2% of the data. An example plot for the feature “Quarter” is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Representative visual dashboard exploring distributions, relationship to flight cancellation status and available values in the categorical feature “Quarter”.

Figure 1: Representative visual dashboard exploring distributions, relationship to flight cancellation status and available values in the categorical feature “Quarter”.

Across categorical variables, I observed some modest associations with flight cancellations. For example, the Year 2020 had a higher proportion of flights cancelled compared to 2018, 2019 and 2021 (5.9% cancellation in 2020 vs. median 1.8% in other years) – likely because of the global COVID-19 pandemic causing travel restrictions. I also noticed earlier quarters 1 & 2 have more cancelled flights compared to later quarters 3 & 4 (Q2=4.6%, Q1=4.1%, Q3=1.7%, Q4=1.1%) (Figure 1). More flights were cancelled in February, March and April compared to other months, and flights were cancelled more often on the 31st day of the month compared to other days. I also observed variation in the proportion of flights cancelled across different departure and arrival states and cities, as well as airline networks. However, these associations appeared less strong than the month/day/year observations.

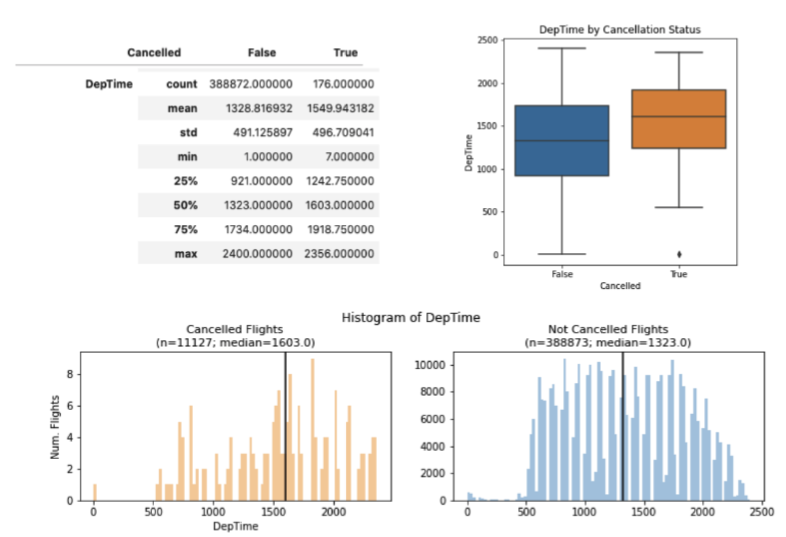

Next, I explored the relationship between continuous features and flight cancellation status. Continuous features examined included: “CRSDepTime”, “DepTime”, “DepDelay”, “DepDelayMinutes”, “TaxiOut” and “Distance”. In addition to tabular summaries, I used two types of visualizations, (1) histograms to visualize the distribution of values between cancelled and not cancelled flights and (2) boxplots to compare the distributions and median values between cancelled and not cancelled flights (Figure 2). Similar to the categorical features (columns), few continuous variables had strong associations with flight cancellation status. Modest associations were observed in departure time (“DepTime”) where cancelled flights appear to have later departure time compared to not cancelled flights (Figure 2). However, the majority of continuous variables had substantial missing data for cancelled flights (ie; a cancelled flight should not have data on in-air flight statistics such as flight time), making them challenging to use in downstream modeling and classification. For example, in Figure 2, there are “DepTime” values for 176 out of 11,127 cancelled (“True”) flights. Given the imbalance in the number of cancelled vs. not cancelled flights, subsetting the data to include only cancelled flights that have no missing information across continuous variables would magnify the class imbalance and pose challenges during classification. Due to this, I opted to use primarily discrete features for my models.

Figure 2: Representative visual dashboard exploring distributions and available values in the continuous feature “DepTime”. Dashboards for all continuous features can be found in the notebook 1_Data_Cleaning_Exploration.ipynb. True = cancelled flight, False = not cancelled flight. Black vertical line on histograms represents the median of distribution.

Figure 2: Representative visual dashboard exploring distributions and available values in the continuous feature “DepTime”. Dashboards for all continuous features can be found in the notebook 1_Data_Cleaning_Exploration.ipynb. True = cancelled flight, False = not cancelled flight. Black vertical line on histograms represents the median of distribution.

Classifiers

File: 2_Classification.ipynb

In light of the number of missing values in continuous variables for cancelled flights, I chose to leverage primarily categorical variables for classification. Specifically, the following 10 categorical and 2 continuous columns were used as features to classify flight cancellation: Categorical = [“Airline”, “OriginalStateName”, “OriginCityName”, “DestCityName”, “DestStateName”, “Year”, “Month”, “DayofMonth”, “DayOfWeek”]; Continuous = [“Distance”, “CSRDepTime”]. First, I subset the data to the desired 12 features and the prediction class (“Cancelled”). I converted “True”/”False” values in the “Cancelled” column to 1 or 0, respectively, to be compatible with classification algorithms. After ensuring there was no missing data across the 12 features, I split the dataset into train (80% of data; 320,000 flights) and test (20% of data; 80,000 flights) subsets. The training data set will be used to generate models for each of the three selected algorithms – Logistic Regression, Naive Bayes’, and Random Forest – while the test subset will be used to assess how well the model can predict whether a flight is cancelled or not (ie., model performance).

Logistic Regression (LR) was the first algorithm I used to predict flight cancellation. To be compatible with the algorithm, I performed one-hot encoding on the 10 categorical features in both the test and train data subsets. One-hot encoding converts each categorical feature into binary, integer-based columns for each class within the feature (ex. [“blue”, “red”, “green”] becomes the columns “blue”=[1,0,0], “red”=[0,1,0], “green”=[0,0,1]). Next, I used the scikit-learn2 implementation of LR to fit a model to predict flight cancellation status using the LogisticRegression() function on the training dataset. I changed the “class_weight” parameter to “balanced” to accommodate for the imbalanced number of cancelled vs. not flights in an attempt to optimize model performance. After fitting the model, I predicted flight cancellation status on the test data subset and saved the predictions for each flight for downstream model evaluation (“results/LogisiticRegression_Predictions.csv”).

I also investigated the utility of Naive Bayes’ Classifier (NBC) to predict flight cancellation status. There are multiple implementations of NBC depending on whether you are using categorical or continuous variables for prediction. NBC is not widely used on mixed datasets with both continuous and categorical features. Since 10 of 12 of my features are categorical, I chose to drop the two continuous variables (“Distance”, “CSRDepTime”) and proceed with using the 10 categorical features as input for NBC. First, I transformed categorical features in both the training and test data subsets into numerical values using the OriginalEncoder().fit_transform() functions in the scikit-learn2 package. Then I used the CategoricalNB() scikit-learn2 function to train a categorical NBC on our discrete feature subset in the training data. Finally, I used the categorical NBC trained on the training subset to predict flight cancellation status on the testing data subset and saved the resultant predictions for downstream model evaluation and method comparison (“/results/CategoricalNaiveBayes_Predictions.csv”).

Finally, I sought to use a Random Forest (RF) as the final method to predict flight cancellation. Similar to LR, I one-hot encoded categorical variables to a series of binary columns to make categorical features amenable to the RF algorithm, and ensure the lack of running relationship between the values within a feature is maintained. Next, I used the RandomForestClassifier() function in scikit-learn2 to train a model predicting flight cancellation status using 100 trees (n_estimators=100) on the training data subset. Finally, similar to the previous two algorithms, I used the trained model to predict flight cancellation status on the testing data subset and saved the resultant predictions for downstream model evaluation and method comparison (“/results/RandomForest_Predictions.csv”).

Model Evaluation

File: 3_Model_Evaluation.ipynb

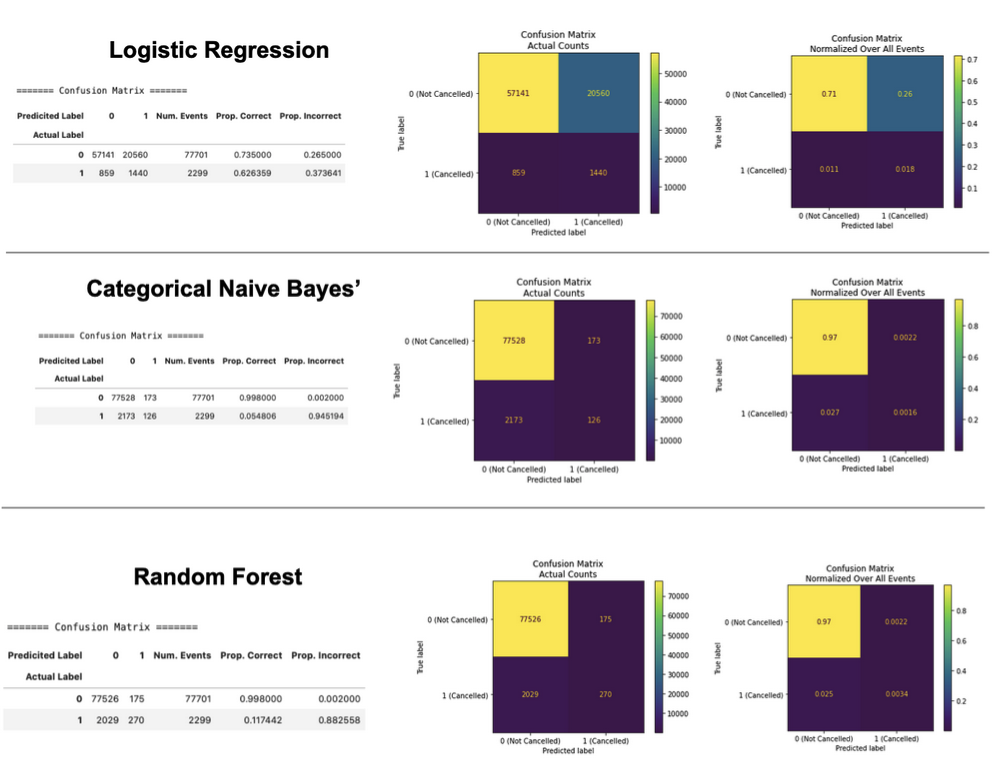

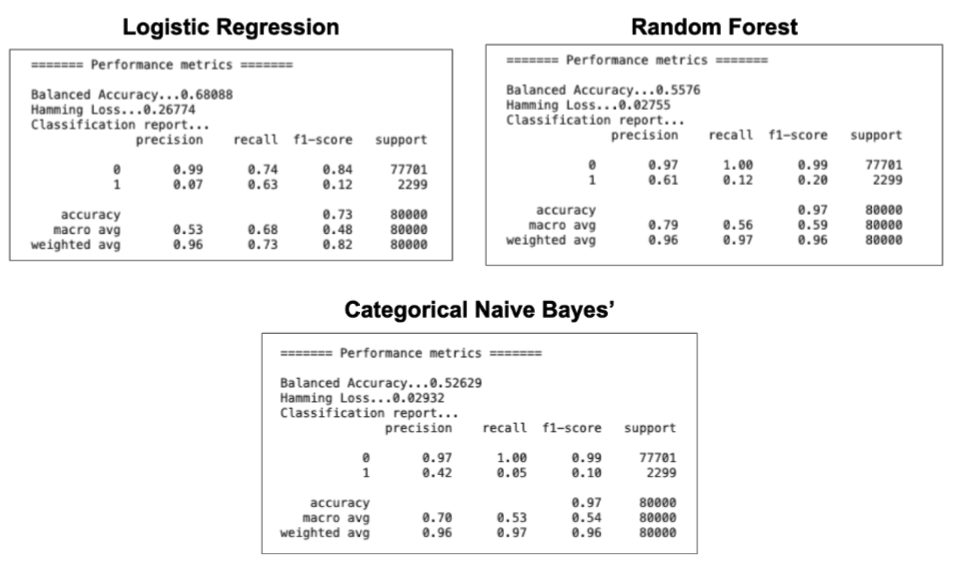

I used 9 metrics to evaluate and compare classification performance between LR, NBC and RF: recall, macro recall, weighted recall, precision, macro precision, F1 score, Hamming loss, accuracy and balanced accuracy (described in Table 2). First, I used confusion matrices to visualize the actual vs. predicted labels for each algorithm to assess the number of correct and incorrect predictions within each class – 1 (“cancelled”) vs 0 (“not cancelled”) (Figure 3). Next, I used scikit-learn2 classification_report(), hamming_loss(), balanced_accuracy_score() functions to calculate desired evaluation metrics across all flights, as well as within each prediction class (ie. cancelled flights only, not cancelled flights only), for each algorithm (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Confusion matrices and heatmap visualizations of actual vs. predicted labels for each algorithm. “0” = not cancelled, “1” = cancelled.

Figure 3: Confusion matrices and heatmap visualizations of actual vs. predicted labels for each algorithm. “0” = not cancelled, “1” = cancelled.

Figure 4: Performance metric reports for each of the algorithms. Metrics are reported across all flights and within each class. “0” = not cancelled, “1” = cancelled.

Figure 4: Performance metric reports for each of the algorithms. Metrics are reported across all flights and within each class. “0” = not cancelled, “1” = cancelled.

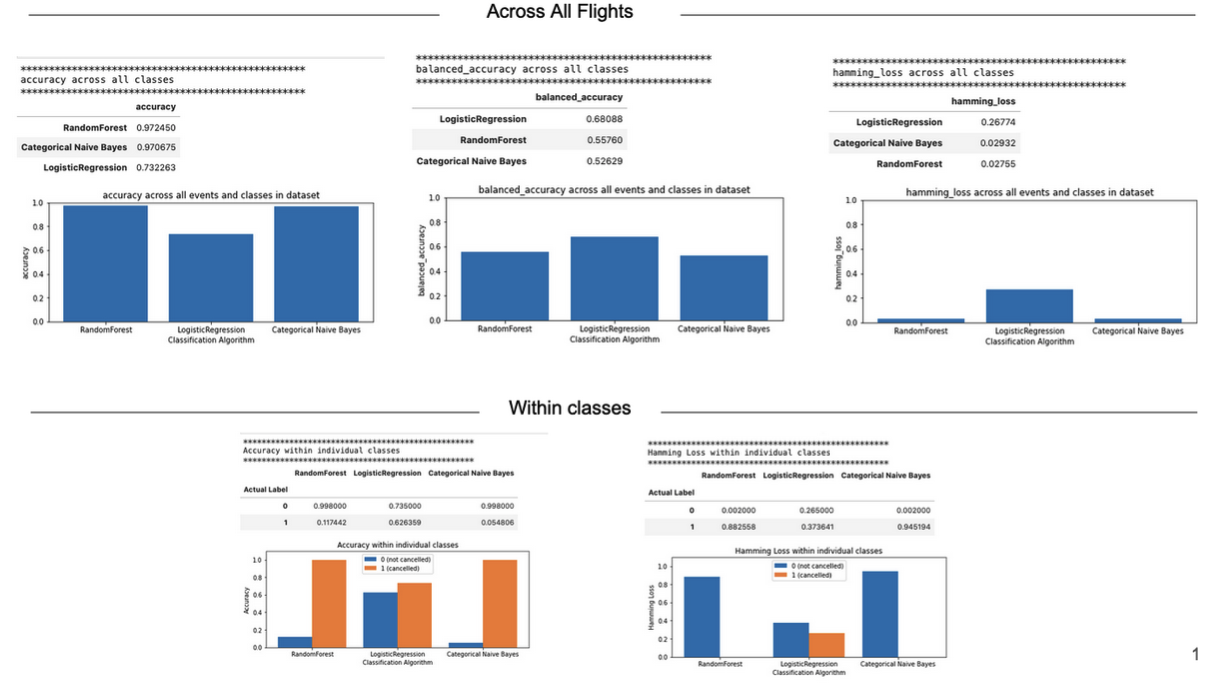

First, I compared the accuracy (number of predictions the model got right) and conversely Hamming Loss (number of predictions the model got wrong) of each algorithm across all flights in the dataset. RF and NBC both had accuracies of >97% and Hamming Loss of <3%, while LR had an accuracy of 73% and Hamming Loss of 27% (Figure 5). Because the dataset is severely imbalanced, with only 2% of the total flights being cancelled, I also looked at balanced accuracy across the algorithms, which takes the mean accuracy within each class – cancelled and not cancelled. This is more appropriate for our dataset because an accuracy of 97%, which looks like a good performance on the surface, could just be predicting all flights as not cancelled and getting a 0% accuracy on the cancelled flights due to the imbalance. LR had the highest balanced accuracy of all three algorithms at 68% (RF=56%, NBC=53%) (Figure 5).

Understanding the caveats of an imbalanced dataset, I next assessed accuracy and Hamming Loss within cancelled flights and not cancelled flights separately to assess performance independently on each of the classes. Not cancelled flights had universally higher accuracy and lower Hamming Loss across all three algorithms, suggesting they are predicted more accurately – which may be influenced by the dataset imbalance as there is more data available to learn on for this class (Figure 5). LR had the best accuracy (62%) for cancelled flights, far surpassing RF (12%) and NBC (5.4%). However, improved accuracy in predicting cancelled flights came at a reduction to accuracy in predicting not cancelled flights where LR was the worst of the three models (74%).

Figure 5. Accuracy and Hamming loss across all flights an within classes (cancelled vs. not cancelled flights) for each algorithm. “0” = not cancelled, “1” = cancelled.

Figure 5. Accuracy and Hamming loss across all flights an within classes (cancelled vs. not cancelled flights) for each algorithm. “0” = not cancelled, “1” = cancelled.

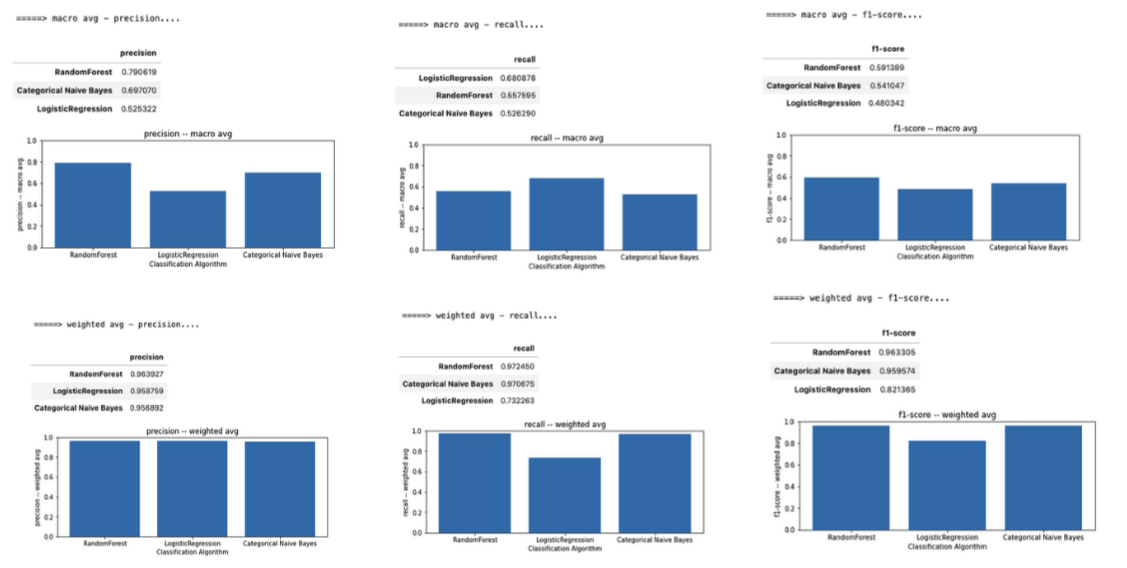

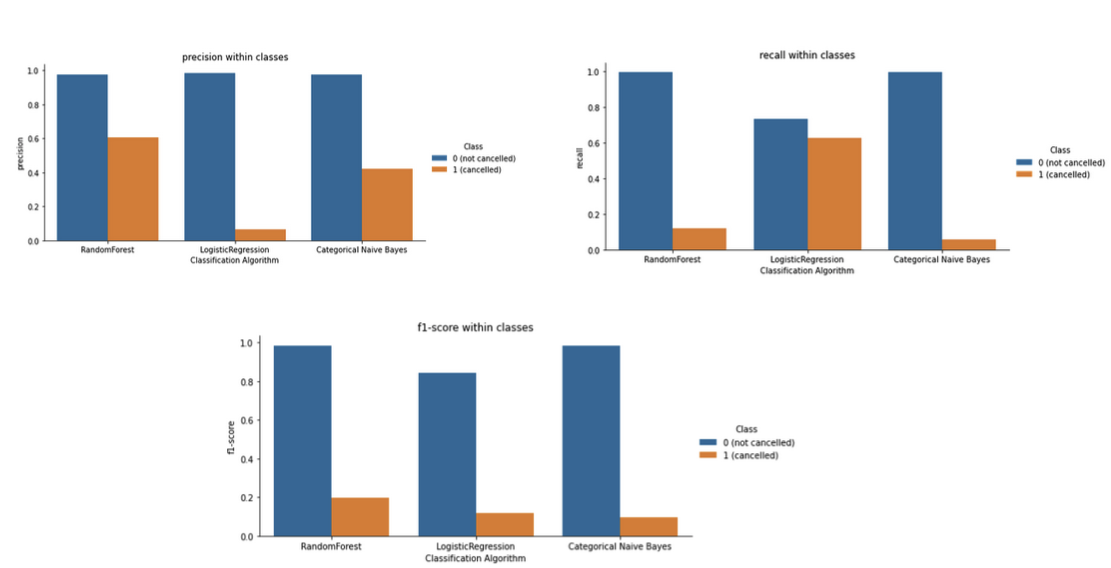

As discussed, accuracy can be deceiving on class-imbalanced dataset like this, where there is a significant difference between the number of “0’ and “1” labels. Accordingly, I used precision, recall and F1 score (Table 2) as supplementary metrics to assess performance. I implemented each of these metrics as (1) “balanced”=“macro” average, where I took the mean metric between cancelled and not cancelled flights and (2) “balanced”=”weighted”, where I took the weighted mean based on class size between cancelled and not cancelled flights (Figure 6). However, because there are so many more not cancelled flights, the weighted values were generally uninformative across values as they washed out signals from cancelled flights. Additionally, I visualized the precision, recall and F1 score within each class individually as grouped bar plots (Figure 7). Similar to the accuracy observations, RF and NBC had higher macro-precision, recall and F1 scores compared to LR – driven by the higher performance on not cancelled flights which make up the majority of the flights in the testing dataset. Within individual flight classes, RF, NBC and LR had universally high precision for not cancelled flights. RF had the highest precision for cancelled flights, while LR had the worst. LR had substantially higher recall for cancelled flights, but lowest for not cancelled.

F1 score is the most informative metric to assess model performance when the classes are imbalanced and unevenly distributed as in this flight dataset. RF has the highest F1 score for cancelled flights (0.196) and not cancelled flights (0.985), making it a contender for the best performing algorithm – even though the score for cancelled flight is still extremely poor (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Macro- and Weighted- Precision, Recall and F1 Score Across All Flights and algorithms.

Figure 6. Macro- and Weighted- Precision, Recall and F1 Score Across All Flights and algorithms.

Figure 7. Precision, Recall and F1 Score within individual classes across algorithms.

Figure 7. Precision, Recall and F1 Score within individual classes across algorithms.

In addition to performance evaluation, it can also be useful to assess memory consumption and run time when benchmarking algorithms to assess their practicality. Although I did not formally record memory or run time, I did observe that RF had a substantially longer run time compared to LR and NBC – suggesting it might be the least appropriate for potential future applications on extremely large datasets. To improve the speed of the RF training, I could have calculated trees on subsets of the data instead of the whole dataset by setting “max_samples” and “bootstrap=True” in the RandomForestClassifier() function2.

Taken together, these metrics suggest that RF is the best of the three algorithms on predicting flight cancellation because it has the highest F1 score, despite LR having the best accuracy. However, in reality, all three of these models had poor performance and struggled to confidently predict cancelled flight status – likely because (1) dataset is extremely imbalanced and (2) the features were not tightly associated with the prediction class as I discussed during the data exploration phase.

Feature Importance

File: 3_Model_Evaluation.ipynb

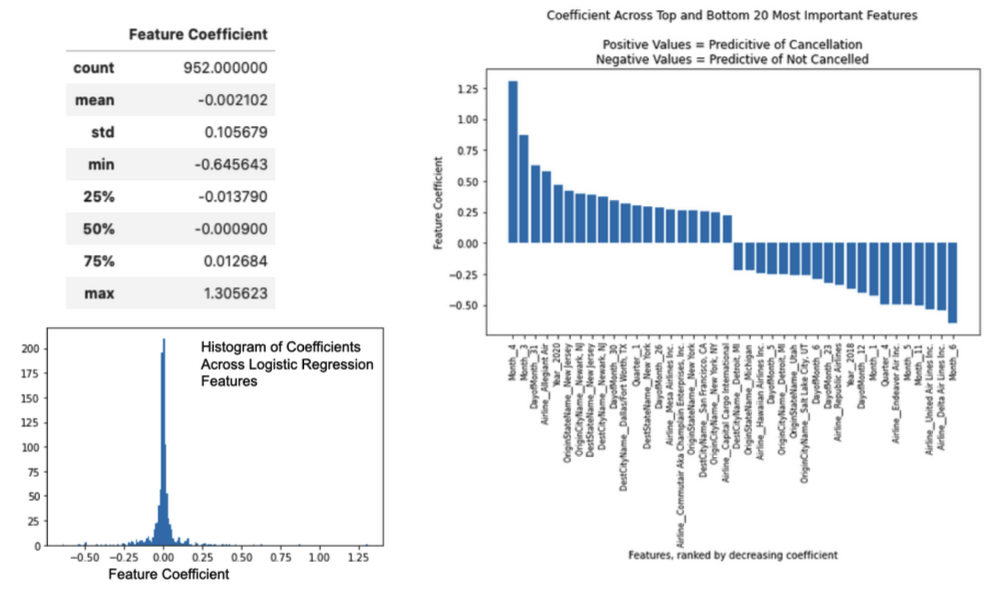

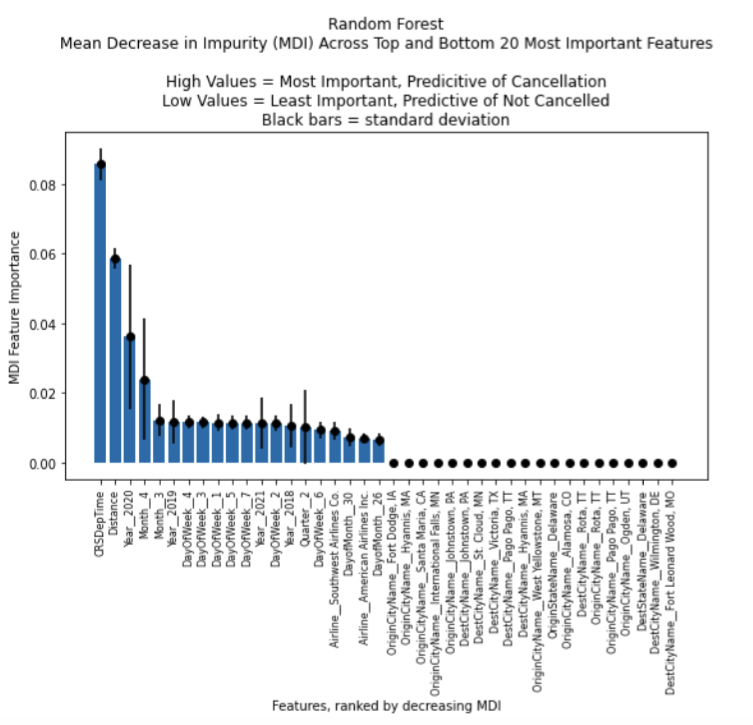

Finally, I evaluated feature importance to identify which features are most predictive of flight cancellation (Table 3). Due to the nature of the NBC, this model was left out of this evaluation, and LR and RF were examined. LR and RF feature importance results can be found in the following respective notebooks “/results/LogisiticRegression_FeatureImportance.csv” and “/results/RandomForest_MDI_FeatureImportance.csv”. I used feature coefficients for LR (scikit-learn2: logReg.coef_.flatten()) features (Figure 8). For RF, feature importance was measured using Mean Decrease in Impurity (MDI) (scikit-lean2: feature_importances_) and standard deviation was calculated from MDI of 100 trees used to the generate the consensus model tree using numpy6 std() function (Figure 9).

The majority of the 952 features used for LR were uninformative, with feature coefficients around 0. The features with the highest positive coefficients – most predictive of flight cancellation – in LR were “Month_4”, “Month_3”, “DayofMonth_31”, “Airline_AllegiantAir”, and “Year_2020”, suggesting flights with positive values for ay of these features were most likely to be cancelled. Interestingly, we see the relationship between year and cancellation appearing again, just as I did in the initial data exploration steps. Features with the most negative coefficients – most predictive of not being cancelled – in LR were “Month_6”, “Airling_Delta Air Lines Inc”, “Airline_United Air Lines Inc”, “Month_11”, “Month_5”, suggesting flights in these months or hosted by these specific airlines are least likely to be cancelled (Figure 8).

By comparing the most important features between RF and LR, I discovered that the same features are not always universally important across multiple algorithms, despite both algorithms using the same feature set during training. For example, “CSRDepTime” and “Distance” are top features predictive of cancellation in RF, but not in LR (Figure 9). There is some overlap, with Month_4 and Month_3 appearing as top important features in both algorithms. As in this example, if only a subset of features are highly important for determining between cancelled and not cancelled, one could subset data to the most important features and regenerate the model to see if it has better speed performance.

Figure 8. Assessing feature importance in Logistic Regression using feature coefficients.

Figure 8. Assessing feature importance in Logistic Regression using feature coefficients.

Figure 9. Assessing feature importance in random forest using Mean Decrease in Impurity (MDI). Black lines represent standard deviation calculated on 100 trees used to generate consensus tree for the model.

Figure 9. Assessing feature importance in random forest using Mean Decrease in Impurity (MDI). Black lines represent standard deviation calculated on 100 trees used to generate consensus tree for the model.

Conclusion

In this project, my aim was to use the specified dataset to predict whether a flight is cancelled or not. I implemented three supervised learning algorithms – Logistic Regression (LR), Naive Bayes’ Classifier (NBC) and Random Forest (RF) – to predict flight cancellation status using data from 400,000 flights equally distributed between the years 2018 - 2021. The dataset was highly class imbalanced – 11,127 (2.8%) flights were cancelled and 388,873 (97.2%) were not cancelled. I used 12 independent features (10 categorical, 2 continuous) to predict if a flight would be cancelled across the three supervised learning algorithms, correcting for class imbalance where possible. Using a suite of model performance metrics, I determined that RF was the best of the three algorithms on predicting flight cancellation because it had the highest F1 score – a metric designed for imbalanced datasets – despite LR having the highest accuracy for cancelled flights. However, all three of the algorithms had poor performance and struggled to confidently predict cancelled flights, likely because (1) dataset was extremely imbalanced and (2) the features were not tightly associated with the prediction class as I discussed during the data exploration phase. Confirming results from the data exploration phase of the project, I found that specific flight months (April and March) and years (2020) were amongst some of the most important features in the model for both LR and RF. If I were to repeat this project, I would look for a dataset with features that were more correlated to prediction labels, and with less class imbalance to boost classification performance. For example, perhaps weather data would be an informative complimentary dataset to help improve flight cancellation predictions. Exploring additional classification algorithms or tuning algorithm parameters are potential avenues to investigate as well.

References

“Flight Status Prediction” Kaggle dataset. Obtained from https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/robikscube/flight-delay-dataset-20182022 in November 2022.

“Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python”, Pedregosa et al., JMLR 12, pp. 2825-2830, 2011.

“pandas: a python data analysis library”, W. McKinney, AQR Capital Management: http://pandas.sourceforge.net

“Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment”, J. D. Hunter, Computing in Science & Engineering, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 90-95, 2007.

“seaborn: statistical data visualization.”, Waskom, M. L.,. Journal of Open Source Software, 6(60), 3021, 2021: https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03021

“Array programming with NumPy.” Harris, C.R., Millman, K.J., van der Walt, S.J. et al. Nature 585, 357–362 (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-2649-2.